In many traditional farming communities, women handle most of the manual work in addition to having responsibilities for home and family management, as many of them have never driven a car. They are consigned to work in planting, weeding, and drying beds while also managing the feeding, education, and healthcare of their immediate and often extended families.

Conversely, men usually take responsibility for operating technology tools, such as tractors and other devices, which also earn higher wages than manual work, and those wages are paid to the men and not always immediately or wholly shared with their families.

Longstanding traditions and practices relating to gender stereotypes and cultural acquiescence have a particular impact on the livelihoods and career opportunities for women in these communities where farming is often the biggest employer (78% of all Zambian women depend on the farming sector).

Numbers from UN research dimensionalise this story:

- Zambia ranked 135th among 187 countries on gender equality, according to the UN, and evidence a dual system of statutory and customary law that tolerated gender discrimination in marriage, inheritance, and access to resources.

- The political participation of women is 116th among 145 countries, according to the same research

- 17% of Zambian girls ages 10-19 are married (compared to 1% of boys), and over a quarter of them have already been pregnant

Olam is committed to challenging this status quo and using AtSource, our sustainability insights platform, we can monitor the impact of our efforts and see where to target further interventions. Our customers have full visibility too, giving them the opportunity to help us influence these elements for the better and meet their own sustainability goals.

The idea to train female tractor drivers on our own estates came from Zimbabwe and South Africa where we’d seen women running large farms, so we knew what was possible. The manager and other leaders of Olam’s Kateshi Estate decided to trial it and recruited six women to train on operating small tractors used to haul water and coffee beans (Kateshi is 2,461.45ha. and is part of the larger 6,985ha. Northern Coffee Corporation Ltd. (“NCCL”).

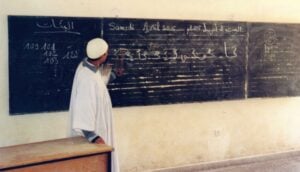

Finding willing volunteers was no problem; in fact, they showed up for the first day of class with their hair done and wearing makeup, as befitting a special occasion. The men on the farm were slightly amused, thinking that the very idea was some sort of joke.

But the women thought otherwise and were quickly proving themselves behind the wheel. A representative from Zambia’s Road Transport Safety Agency (RTSA) joined to help educate them on maneuvering and road safety. Word quickly spread in the community and more women asked to join the programme.

To understand the effect this new line of work has had for these women’s position in their households and communities, as well as female empowerment more broadly, we commissioned a study last year, led by a social research consultant at the University of Bern, Switzerland. The data applied a mixed method approach using qualitative and quantitative methods based on data triangulation. 83 women were interviewed and/or engaged in focus group discussions, along with 60 men and children to understand the perception of the initiative of the wider communities around the NCCL estates, as well as to establish a typology of household decision-making in the area.

Its main findings were:

- Significantly increased economic well-being and autonomy of female tractor drivers

- Significantly increased decision-making power of female tractor drivers on household and community levels

- Increased respect, self-esteem and dignity, as well as a feeling of having control over their own lives, being independent, and occupying “the decision-making space.”

In the qualitative interviews, all of the female drivers strongly emphasised economic empowerment as the prime benefit and that it positively impacted all of the other indicators of gender quality and empowerment. The quantitative responses from both men and women confirmed these observations, ranking economic improvement first among the benefits.

Just as significantly, 39% percent of the women drivers living with their husbands reported that they maintained some level of control over decision-making on how the income they earned is spent, 38% reported control over half, and 23% said that they have full autonomy on how the funds are used.in family households including female drivers, suggesting a renegotiation of household responsibilities between husbands and wives.

This economic empowerment enabled them to pay for schooling for their children, support relatives, improve housing, buy better quality food, and diversity their livelihoods by investing in other income-producing activities.

Importantly, there were no increased burdens or negatively perceived increased responsibilities for the women tractor drivers; they managed to balance household and work responsibilities by getting help of relatives whom they renumerated by supporting their education, for instance. This helped to control the workload.

Perhaps more promisingly, many impacts of the programme were seen as generational, as both male and female quantitative responses ranked highly the motivation the initiative provided for other women and younger girls to engage in economic activity outside of the home (like selling clothes or opening small shops). Many of the young girls who participated in focus groups as part of the study said they saw driving tractors as a stepping stone to financing higher education, and 98% of the female participants said they’d allow their daughters to become tractor drivers.

What did we learn about implementing an effective programme? After training 76 women by the end of 2020, I think there are three lessons that we’ll factor into our next efforts:

- First, it’s not enough to rely on women’s inherent resilience to find the time and capacity to engage in self-improvement. The women drivers who participated in our programme did so at great expense to themselves, as they were not excused from their “day” jobs nor from their responsibilities at home. They succeeded because of their raw determination but making such programmes available to more women might require more direct and indirect support (like opportunistic day-care during class, for instance).

- Second, challenging the status quo means changing how men think and act, not just empowering women. What started as dismissal or mild derision from men when training started, morphed into denial and sometimes outright hostility as women were able to take jobs that paid more. Including men in this evolution of gender roles is crucial and could involve a wide variety of educational and/or socialisation activities.

- Third, and finally, initiatives and studies are only moments in time, and it’s important to take note of the results and take subsequent action. AtSource, Olam’s sustainability insights platform, for agricultural supply chains, provides visibility into a number of factors that impact farmer livelihoods and insights into how customers and other stakeholders can collaborate on improving work and life conditions.

What’s clear from our survey is that women driving tractors can be meaningful agents for change.