NOTE: the situation globally and especially in the low-income urban communities discussed in this article is evolving rapidly. The survey and conversations informing this article were primarily conducted from 15 April, 2020 to 15 May, 2020.

At Archipel&Co, our inclusive business work has been committed to collaborating with residents from low-income communities whose creativity, courage and skills provide crucial local knowledge and insight often mis- or under-represented in mainstream business. We share this snapshot of how the COVID-19 crisis is impacting the daily lives of those living in low-income communities in the hopes that it might inform public, social and private sector understanding and response. It is not a full picture, but we hope it adds to the conversation. Most importantly, this is about ‘hearing’ from those whose voices are too often marginalised.

Thanks to our local teams and partners in several neighbourhoods in India, Kenya and Côte d’Ivoire (many collaborators and alumni of our Community Voices approach), we conducted a qualitative survey of 198 individuals and have had weekly exchanges with key contacts since March to better understand local perceptions and experiences of Covid-19 and the lockdown measures put in place.

1. Rapid adaptation to social distancing and lockdown rules, despite challenges associated with dense living and shared spaces.

Despite the challenges and risks low-income residents navigate on a daily basis, 81% of respondents stated that social distancing is the most effective way to protect themselves from the virus, and our respondents remarked on the efforts of urban residents, pedestrians, bus commuters, and shop keepers to respect the instructions related to social distancing.

A combination of social distancing measures have taken place, partly self-organised and partly imposed by the state. For example, daily travel has been considerably reduced (54% of respondents have completely stopped using public transport since the beginning of the crisis and 24% use it less than before). At the same time, one micro-entrepreneur based in Eastleigh, Naiirobi remarked “matatu [mini-bus] are carrying one person per seat, plus you have to wash your hands before you get in.” Makeshift hand-washing stations were set up at speed using re-purposed “jerrycans” to ensure riders had access to “micro-hygiene” points.

The lack of reliable basic services in under-served neighbourhoods has long been a challenge for low-income urban residents. Covid-19 has made it even more difficult to safely access basic services. 53% of respondents say that basic services have completely stopped or sharply reduced in their neighbourhood as a result of the crisis.

One critical challenge in accessing basic services regards sanitation. A large majority of urban residents share communal toilet facilities (more details here). In the absence of alternative solutions, and despite the lockdown, many residents have no alternative but to use communal public toilets, or shared water points – where physical distancing and strict hygiene measures are difficult to apply.

2. Worries concerning livelihoods and food security are greater than fears of getting COVID-19 itself.

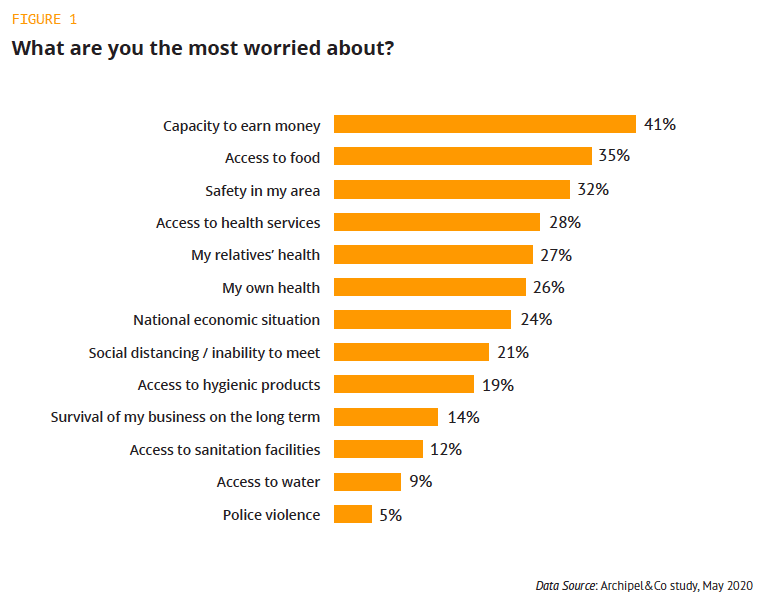

Like everyone around the world, COVID-19 has our respondents gravely worried. However, as Figure 1 shows, they are less worried about the risk of falling ill and more so about the livelihood and safety impacts of the lockdown response. As 31 year old Amrit from Pune, India shared, “Of course, I’m afraid of getting sick. But I’m also worried about…if it goes on like this for 1 or 2 months, the economic crisis will really start.“

Like Amrit, most residents living in low-income neighbourhoods work in the informal sector. They have no social protection and must work today to eat tonight. Many are savvy micro-entrepreneurs who have diversified income streams to survive and thrive despite normalised volatility and uncertainty. Given the systemic nature of this shock, many are seeing dramatic income drops. 58% of those surveyed have been forced to stop working completely and 26% have had to reduce their level of activity since the start of the confinement. On average, those who are working now earn 72% less than before the crisis. Behind these figures are a very real hunger impact and a growing food security crisis. As Issouf from Abijan, Ivory Coast explained, “If it’s not the virus that’s killing us, the hunger will”. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), three quarters of informal workers – 1.6 billion people – could see their incomes wiped out by the crisis.

We also note that the measures put in place in some neighbourhoods by residents themselves, with or without the support of public authorities, NGOs or international organizations – from installation of temporary water points to the distribution of hygiene products in particular – are perhaps the most effective. 46% of our respondents consider that it has become easier to wash their hands with soap in their neighbourhood since the beginning of the crisis.

At the same time, we must resist the clichéd trope about the resilience and agility of the informal sector and slum-dwellers, no matter how true, lest it be misinterpreted as these communities not needing support. One of the key questions we are grappling with at the moment is what will the nexus of business, social innovation and development look like in the weeks, months and years to come, and how can we best prepare for that collective enterprise and challenge?

Authors: Justin DeKoszmovszky, Pauline Lebas, Maureen Ravily (of Archipel&Co) and Tatiana Thieme (associate professor in geography at University College London)

Contributors: Atrayee Das Chaudhuri, Vinod Ghule, Arouna Kouassi, Titouan Bordas.

Editor’s Note:

This article is adapted from an original piece available here.

This article and its underlying data are not intended to be exhaustive or statistically representative. Our aim is to shine some light on the lived experience and amplify the voice of slum-dwellers who are too often forgotten – in general and even more so in the current crisis – despite being among the most brutally affected. We thank them warmly for agreeing to answer our questions and helping us understand.

Archipel&Co will continue to share what we know about the impact of the crisis on the informal, precarious and marginalised in an effort to improve the public, social and private responses. We are particularly keen to find partners with whom we can investigate the impact on key sub-segments (e.g. informal waste-pickers, community sanitation workers, smaller farmers). To that point, we are currently gathering data from small farmers and rural animal health professionals and will soon be sharing those results.

For further information and access to the full survey results, please contact us: ju******************@ar*********.com and ma************@ar*********.com

Archipel&Co is donating to local efforts in the communities where we work and live and we are happy to connect anyone interested in also supporting these efforts.