Human rights and climate change are increasingly understood as issues that are inherently linked. The UN Secretary General, António Guterres, stated earlier this year that the climate crisis presents the biggest threat to our survival as a species and is already threatening human rights around the world.[1] Similarly, any action taken to achieve a low-carbon economy without consideration for human rights will only exacerbate existing inequalities and increase the potential for exploitation of already vulnerable groups.

While decisive action on climate change is imperative, the implications of making such radical changes to the economy must also be considered. A requirement of the Paris Agreement is to achieve a ‘just transition’ – a future where no one is left behind in the movement towards a low-carbon economy. Early action can minimise the negative impacts and maximise positive opportunities. A just transition must, therefore, address the human rights implications of the decarbonisation and energy transformation, ensuring that workers and communities are at the centre of this vision.

Urgent need for companies to improve and align their actions on human rights and climate change

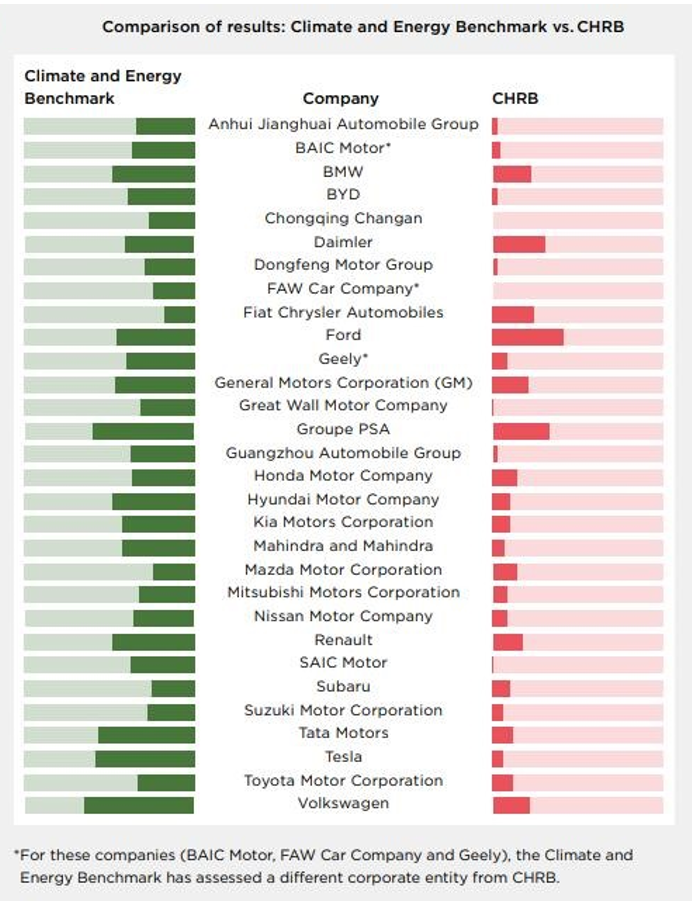

The 30 companies assessed in the 2020 Automotive Performance Update were also included in the 2020 Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB), which provides an iterative snapshot of companies’ policies, processes and practices in place to systemise their human rights approach and how they respond to serious allegations. This has allowed WBA to assess automotive companies’ performance regarding their efforts to advance the low-carbon transition as well as promote human rights.

When comparing both assessments, the results are alarming. Almost no correlation could be found between the companies’ relative performance on either benchmark, suggesting a disconnect between their disclosures as well as their actions on climate and human rights issues (Figure 3 below). Some companies that demonstrated action on climate issues, such as low-carbon transition plans, emissions reduction targets and climate change oversight, disclosed very little, if any, information on how they manage human rights, and vice versa. This lack of correlation suggests that many automotive manufacturers still consider climate and human rights issues separately to be addressed independently of each other, despite the fact that they are increasingly recognised as interconnected. In the coming decades, emissions-intensive sectors, such as automotive, face the major challenge of shifting to a low-carbon economy while upholding the central promise of the Sustainable Development Goals to leave no one behind. Demonstrating success in both areas is paramount to ensure a just transition.

[1] UN Secretary-General’s remarks to the UN Human Rights Council, António Guterres, 24 February 2020

Figure 3: Comparison of results: Climate and Energy Benchmark vs. Corporate Human Rights Benchmark 2020

Severely lacking supply chain management

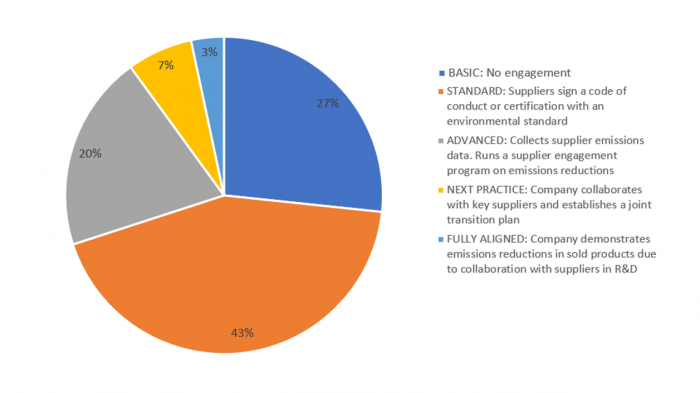

A key area of weakness for the automotive sector in both assessments is supply chain management. In the 2020 Automotive Performance Update, more than half of the companies assessed showed no evidence of proactively driving emissions reductions throughout their supply chain in either the manufacturing or vehicle in-use phases, and a quarter of companies did not engage their suppliers on greenhouse gas emissions or broader climate change issues at all.

Only three companies are either fully aligned or meet ‘next practice’ requirements regarding supplier engagement on climate issues, indicating collaboration with key suppliers on a joint transition plan. Some companies exhibit good practice of supplier engagement:

- BMW requires all new suppliers to implement a certified Environmental Management System in accordance with international environmental standards ISO 14001. It also aims for 60 percent of suppliers to participate in the CDP Supply Chain program and achieve at least a B rating from CDP by 2025. Furthermore, the company is collaborating with Swedish battery manufacturer Northvolt and Belgian battery materials developer Umicore to develop battery cell technology.

- Groupe PSA uses an external contractor to assess suppliers’ environmental performance and requires suppliers to monitor current and future carbon dioxide emissions as well as contractually commit to emissions reductions.

Figure 4: Level of engagement with suppliers (by percentage of the 30 companies assessed)

Similarly, the CHRB found that 27 out of the 30 automotive companies failed to set core expectations through contractual arrangements with suppliers on risks like forced labour and child labour, and only one company – General Motors – mapped its direct and indirect suppliers for major components. As companies begin to shift towards greener power, demand for energy storage in the form of batteries is expected to grow, particularly in the electric vehicle market. In this context, a lack of supplier engagement, especially in the areas of forced labour and child labour, is concerning. The minerals present in batteries are often sourced from politically unstable locations and have been linked to pervasive human rights abuses, including child labour. The CHRB found that only nine automotive companies disclosed any information relevant to responsible mineral sourcing, such as working with smelters or refiners or identifying and managing risks within their supply chain.

To measure the private sector’s performance on achieving a just transition, WBA will assess 450 companies on their contribution to a just transition between 2021 and 2023. The methodology will be informed by existing knowledge and expertise in the areas of human rights and climate change. It will draw on three years of benchmarking experience by WBA and will be developed through an open and inclusive multi-stakeholder engagement process. All information and data produced will be publicly available for stakeholders, highlighting areas where they can positively leverage their influence and where urgent action is needed.

This article was previously published on the World Benchmarking Alliance website.

Read more from the World Benchmarking Alliance here and on Human Rights here.