The phenomenal growth of mobile technology in Africa with apps such as M-Pesa and Eco-Cash has made banking possible even for my 91-year-old grandmother, who lives in a Zimbabwean village. This grassroots approach to innovation has opened up tailored and useful apps to mobile phone users across the African continent. My grandmother now even has an app on how to herd cows!

So as an African clinician and researcher in global mental health, I have started to examine how we might use technology to narrow the treatment gap for mental, neurological and substance use disorders on the continent. There is a pressing need to address these conditions in low- and middle-income countries where people currently have little prospect of being treated. In particular, there is a need to focus on depression, which, according to the World Health Organisation, is the leading cause of disability globally with more than 300 million affected and over 70 percent of these coming from low- and middle-income countries like Zimbabwe.

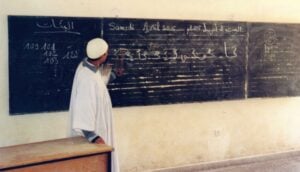

I live and work in Zimbabwe, a country with a high literacy rate and mobile phone penetration, but also high levels of poverty and an estimated 20 percent rate of depression. As most Zimbabweans have little access to treatment, I was in charge of a local team that set up the Friendship Bench in 2006, a locally developed talk therapy program delivered by trained grandmothers. The Friendship Bench programme has proved successful in reducing symptoms of depression and suicidal thoughts. The grandmothers, who are all trained in the basic principles of cognitive behaviour therapy with emphasis on problem solving, are provided with support by psychiatrists and psychologists via mobile phone platforms such as Skype and WhatsApp. So it seemed that the obvious next step was to explore the possibility of developing a mobile app that might reach even more people, particularly in remote areas. Unfortunately, the evidence suggests it may take some time to get it right.

Although ”mHealth”—the use of mobile phones and other wireless technology in medical care—in Africa is growing with apps such as Hello Doctor, MDConsults, MomConnect and Aviro Health, most mHealth apps focus primarily on improving and reducing cost of patient monitoring through better digital surveillance, data collection, and utilisation of SMS messaging. In fact, a recent study showed that mHealth in Africa emphasizes empowering health workers through improved clinical decision support with little or no opportunity for interactive platforms for patients. We need to start thinking of client-focused interactive apps which seek to empower the user through real-time feedback. For instance, a self-report questionnaire could enable a client to be aware of their symptoms which will provide them with immediate options on what possible help is available for the given symptoms. This could be linked to health workers in the community who could act as a support system.

In my research, I’ve found that interactive apps focusing on mental health disorders are virtually absent from the market, except for an app developed by the South African federation for Mental Health. Many of the apps that include mental health as a component, rely on SMS texts and information dissemination. But a study we conducted last year found that SMS messaging was inferior to a one-on-one talk therapy for people suffering from depression. This has been the key motivator to develop a more complex and interactive Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) based app.

But the question remains: Would a complex, user-friendly CBT based app lead to an increased use by people living with depression?

According to academic Kentaro Toyama, based on his experience in India, Bangladesh and schools in California, technology works best when people are motivated, committed and have sufficient time to use it. And this is precisely opposite to many of the characteristics of depression, such as difficulty in concentrating, lack of motivation, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness.

This line of thinking is echoed by the grandmothers working on the Friendship Bench in Zimbabwe. According to Ambuya Chinhoi, a 76-year-old grandmother working with Friendship Bench for 10 years, “people will not use their smart phones to improve their lives until their minds are opened up and this requires initial human interaction.”

Fundamentally, we are social creatures that thrive on positive human contact and this seems to be an important component in the initial treatment of depression. According to leading anthropologist, Helen Fisher, human contact has been critical to our existence since our days in hunter gatherer communities. In recent years neuro-imaging of the brain has revealed that the frontal lobe contains mirror neurons which apparently respond to human interaction positively through empathy. Mirror neurons enable us to share the emotions of others by partially processing them with our own emotional system.

There is an increased realization in our fragmented world that one-to-one contact with a real human being is important for nurturing the human spirit and mental health. For instance, the verdict of the longest longitudinal study that has been following over 700 families since 1938 is that: positive human contact and relationships make us happy and live longer!

So, despite my continuing determination and optimism to find a fully satisfactory technical solution to depression, the most important task right now is to continue helping people through face-to-face interactions.

Dr. Dixon Chibanda is a psychiatrist from Zimbabwe and Aspen New Voices Fellow. Follow him on Twitter @DixonChibanda