This requires having a clear Purpose, which is authentic and inspiring, explains why the business exists and how it creates value for itself and for society. It is about having a comprehensive Plan, which minimises negative social, environmental and economic impacts, maximises positive impacts and covers all aspects of the business and extends into the supply-chain. Going All In means having a sustainable Culture, which is innovative, empowering and engaging, open and transparent, and with a core sense of ethics and responsibility. Fourthly, it is having the skill and will to Collaborate extensively with a range of business, civil society and public sector partners. And, lastly businesses need to act as Advocates, speaking out and up for social justice and sustainable development.

We emphasize that all these five attributes are crucial. Each helps to reinforce the others. Each needs the others in order to work. Together they allow for ambitious sustainability leadership. So, for example, a good Plan or strategy for sustainability is supported by an appropriate organizational Purpose. The Culture of the business determines how well the plan is implemented: do employees and other stakeholders really get behind it, because the company engages and empowers them and is transparent about what it is trying to achieve and what it needs from stakeholders. An ambitious sustainability Plan will require a range of Collaborations with a variety of partners: other businesses, NGOs, social enterprises, governments, communities, and sometimes academia. And an ambitious Plan will involve the company trying to persuade other businesses to get involved both through its example and its Advocacy.

What makes a good Plan?

There are several Critical Success Factors for a good Sustainability Plan or Strategy. These include:

- Being comprehensive and internally consistent; covering all core business activities; integrated across functions, strategic business units and markets

- Articulating a compelling business case based on sustainability

- Including stretch goals based on science (e.g. see www.SciencebasedTargets.org) and aligned with the SDGs as well as clear metrics and measurement, and timely reporting and disclosure

- Ensuring that it is championed and driven by top leadership who are constantly re-selling the Plan with the new data and examples required to keep it fresh

- Pursuing it persistently, even through adversity, and being responsive to changing societal expectations

- Ensuring organisational rewards e.g. bonuses and resources are aligned with delivery of the Plan

Crucially, there will not be inconsistencies between the sustainability plan or strategy and the overall corporate strategy. Indeed, increasingly over time, these two will become one and the same.

How does a good sustainability Plan emerge?

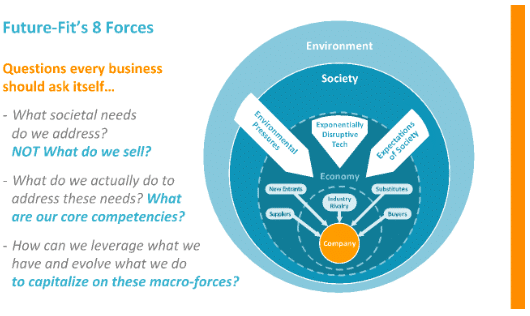

Nowadays, for most companies, in most sectors, in most parts of the world, a Plan is unlikely to come, so to speak out of nowhere, with no antecedents. In practice, companies, whilst they may not have formulated an explicit Plan or strategy for sustainability, they will already have a number of specific projects and initiatives. Turning these into a more systemic Plan, signals a more serious intent, identifies gaps and weaknesses, gives a focus and raised profile, allocates resources and can generate wider interest and support. Typically, a more systematic Plan will be based on some form of materiality assessment. Dr. Geoff Kendall, founder of the Future-Fit benchmark, talks of extending Porter’s traditional five forces, instinctively recognized by business-school-trained managers across the world, into eight forces: crucially adding social, environmental, and technological forces.

This is the basis for the open-source Future-Fit Benchmark. A Future-Fit® society will protect the possibility that humans and other life can flourish on Earth forever, by being environmentally restorative, socially just and economically inclusive: http://futurefitbusiness.org/

Businesses can also use a six-S toolkit in order to identify risks associated with negative social, environmental and economic (S.E.E.) impacts and opportunities from increasing positive S.E.E. impacts:

- SCOPING versus Impact Areas (e.g. Impacts in Workplace, Marketplace, Environment and Society) / responsibility issues

- Stakeholder surveys: SWANS AND OWANS: Stakeholders Wants & Needs & Organisation’s Wants and Needs of stakeholders

- Sectoral competitors / specialist trade associations & sectoral sustainability initiatives / Sustainability Accounting Standards Board: www.sasb.org which all offer sectoral-specific guidance on material sustainability issues

- Sustainability leaders’ published reports

- Scenario-planning such as BSR (Business for Social Responsibility) scenarios: Doing Business in 2030 – Four Possible Futures

- SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals opportunity analysis: The UN Global Compact together with the Global Reporting Initiative and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development have produced The SDG Compass. This guides companies on how they can align their Sustainability Plan / strategies as well as measure and manage their contribution to the realization of the SDGs. The SDG Compass presents five steps that assist companies in maximizing their contribution to the SDGs: understanding the SDGs, defining priorities, goal setting, integrating sustainability and reporting. https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/3101

Telling a story

Joining together this myriad information and data, enables a business to determine its current “today” position and – depending on the scale of the company’s ambition and sense of responsibility for its impacts – its desired “tomorrow”. This is the scientific or left-brain approach. Inspirational plans, however, also need a right-brain phase as well. It is not a coincidence that there is growing interest in the art of storytelling for business – not least in the context of embracing sustainability. Numbers, it is often said, “numb us!”. It is hard for most of us to grasp the significance of avoiding x tons of waste to landfill, or x tons of C02-equivalent emissions into the atmosphere. That is why most of us need analogies such as “that’s the equivalent of four football pitches” or “that’s enough to light up New York city for a year”.

Great sustainability plans don’t just set a direction and establish some BHAGs: Big, Hairy, Audacious Goals. They also tell an inspiring story. One of the best corporate sustainability storytellers was the late, great Ray Anderson – the founder of Interface – the floor coverings business that he set up in Georgia, in the southern USA in the 1970s and built into a billion dollar business, before realizing in 1994 that he had to make a “mid-course correction” and committed thereafter to run Interface sustainably. Successive iterations of the Interface sustainability plan tell a story, using the metaphor of climbing a mountain: Mount Sustainability. See visual.

Today, Interface has embarked on a new story around Climate Take Back, an attempt to reverse global warming: “If humanity changed the climate by mistake…we can change it with intent.”

A comprehensive Plan for sustainable business: The Unilever Sustainable Living Plan

In 2010, Unilever launched its Sustainable Living Plan (USLP) with a pledge to double the size of the business whilst halving its environmental footprint—subsequently modified to halve the environmental footprint of the making and use of Unilever products by 2030 as it grows its business. This was and remains a ground-breaking commitment. The USLP also included bold targets to improve health and well-being for more than one billion people by 2020 through health and hygiene initiatives and by improving the nutritional content of its food products to encourage healthier diets, for example with cuts in salt, saturated fats, sugar and calories. The company also committed to enhance the livelihoods of millions of people, including linking more than 500,000 smallholder farmers and small-scale distributors in developing countries to its supply chain.

Like other companies with comprehensive and ambitious sustainability plans, the USLP has forced Unilever into a radical overhaul of relations with suppliers. Unilever’s approach has long included ‘the total value chain’ as Section 4 of the company’s Social Review 2000 – the company’s first social report – makes clear. Still, the SLP raised the bar. The Responsible Sourcing Policy launched in 2014 and revised in 2017 further sets out standards required of suppliers, auditing processes depending on the historic performance of the supplier, and rigorous processes for reporting and remedying violations of the policy. Alongside the ’stick’ of higher performance standards, has come the ’carrot’ of extensive capacity-building programs to help suppliers improve their performance and profitability. The USLP provided the goals and programmatic approaches to drive sustainability performance and is foundational to Unilever’s strong reputation as a leader. The company is now preparing to launch a new version of the Plan for the 2020s. As Alan Jope, Unilever’s new CEO has declared: “I intend to build further on Unilever’s century-old commitment to responsible business. It is not about putting purpose ahead of profits, it is purpose that drives profits.”

Ten critical questions to assess a sustainability Plan

As many more businesses develop their own sustainability plans, what questions should they ask themselves about their proposed plans? What should employees, investors, activist NGOs and others interested in the role that business can play in improving planet and society, ask?

- Is Plan part of overall Corporate Strategy and increasingly becoming the strategy?

- Is it comprehensive: Does the Plan cover the core activities of the business?

- Are senior leadership championing the Plan?

- Is it coherent – for example, are incentives re-aligned with the Plan?

- Is it consistent over time and with external positioning e.g. with lobbying undertaken by business representation organisations that the business is part of?

- Is it ambitious: are targets, for example, science or evidence-based (certified by the Science-based Targets partnership)

- Are the organisation and individual employees managed and measured against the Plan?

- Is the Plan robust so that over time, there is a realistic road-map to transition from unsustainable raw materials, products, processes, behaviours, activities?

- Does the Plan extend to the supply chain with progressively higher standards being required?

- Does the Plan have a credible time-horizon for engaging customers and consumers and for Extended Producer Responsibility?

Does a Plan pay?

For at least 30 years, business people, politicians, journalists have been asking “but does it pay to become more responsible and sustainable?”. The good news is that indeed it does and there is growing evidence to prove this. See for example, a February HBR blog by two leading, young business school professors Ioannis Ioannou and George Serafeim:

Yes, Sustainability Can Be a Strategy FEBRUARY 11, 2019

Ioannou and Serafeim describe a new paper they have produced which uses “data from MSCI ESG Ratings, the largest provider of ESG data in the world, for the period 2012-2017 for all companies that appear in the MSCI consistently across all years — i.e. about 3,802 companies…” For each industry they identify the set of sustainability practices upon which companies converge over time — which they term “common practices” — and those for which they do not — which they term “strategic.” Ioannou and Serafeim write that their “exploratory results confirm that the adoption of strategic sustainability practices is significantly and positively associated with both return on capital and market valuation multiples, even after accounting for the focal firm’s past financial performance.”

They conclude that “sustainability can be both a necessity and a differentiator. Some sustainability activities are simply becoming “best practice” and so are a necessity. But the data suggests that some companies are creating real strategic advantage by adopting sustainability measures their competitors can’t easily match.”

Conclusion

Leading companies recognize it is no longer a choice between profits or sustainability. Rather the choice is better, long-term profits through sustainability or inferior profits – which are unsustainable – in every sense of the word. Planning for enduring leadership requires sustainability to be at the heart of any global company’s strategy.

David Grayson is Emeritus Professor of Corporate Responsibility at Cranfield School of Management; Chris Coulter is CEO of GlobeScan; and Mark Lee is Executive Director of SustainAbility. This article develops and updates a chapter from their recent book “All In: The Future of Business Leadership” (Greenleaf/Routledge: 2018) www.AllInBook.net